”Fortum’s financial targets and dividend policy remain unchanged. The long-term over-the-cycle financial targets are: Return on capital employed (ROCE) at least 10%”

Who has decided on such a goal and has anyone bothered to think whether or not it is consistent with climate goals? Why 10% and not say 7.3% or 13.5%? Is there any other reason for this than the simplicity of counting with 10 fingers? In this post I discuss how high expected returns on capital hinder climate action. Expected returns are not a consequence of some ”optimization” or ”science of economics”, but rather derive from the actor’s sense of entitlement. Why the rest of the society should simply accept this is an interesting question especially since this dominates the cost of decarbonization. Who decided that this should be taken as given? Should he/she be fired? Why should climate action be conditional on 10% returns on the invested capital? Why should one even get 10% returns on building and maintaining long-lived infrastructure that must largely be rebuild in order to stop the climate change?

When something of critical importance must be done, the first reaction should not be computing the return on investment. After all, whoever approaches the issue in this way has demonstrated that the issue is of lesser importance. But of course, nuances exist. It might be that at the societal level we see the action as necessary while at the same time we understand the need for private companies to make a profit. It could be that under such circumstances society takes responsibility for the project, defines the goals, and maybe buys some parts of the project from private companies if that is seen as useful. This has been the norm during war times, for example. Also, in large parts of the world basic health care and education are conducted around policies set by the state independent of whatever expected returns some financial types might desire.

The purpose if this post is however to sketch how profitable investments on climate action might be from the investors perspective. In my earlier post I noted how, for example, the cost of energy as well as net present value of the project depend critically on how patient and far-sighted the investor is. An investor looking for profits will estimate climate action as unprofitable while a patient investor using a lower discount rate will detach from fossil fuels. I continue partly on similar lines, but now I also compare the expected returns for different sources of electricity and discuss what implications this has for the climate policies.

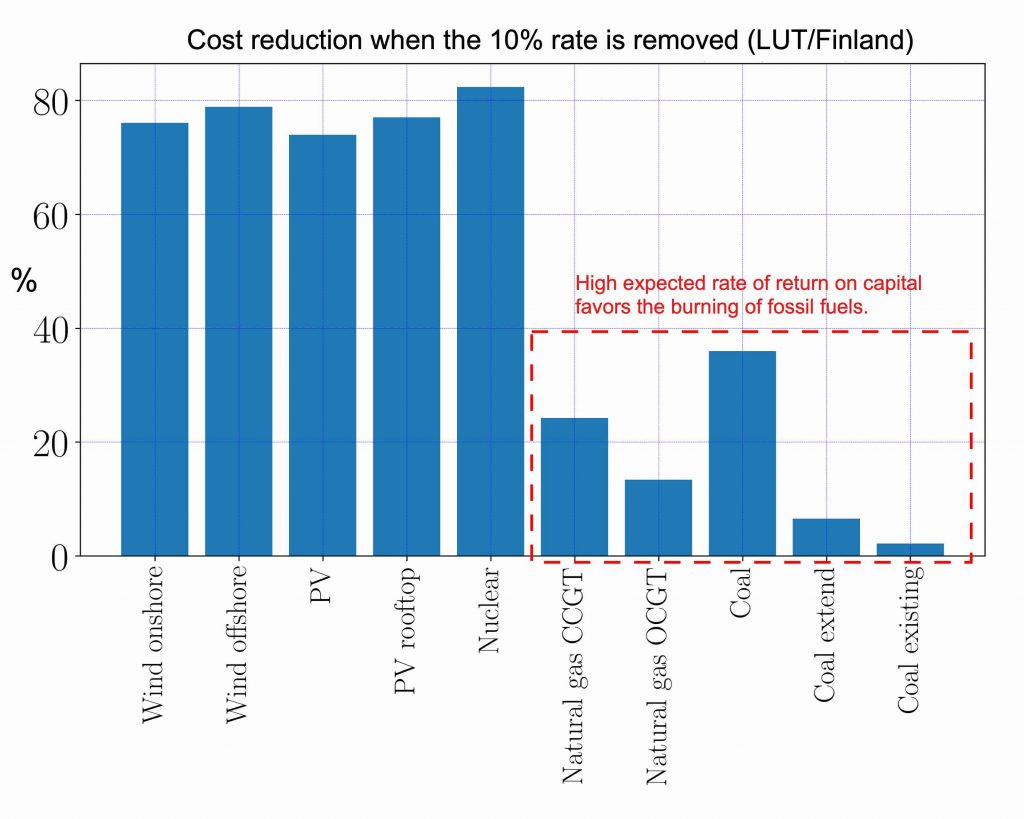

For example, Fortum, largely Finnish state-owned energy company, has a 10% goal for the returns on invested capital. Vattenfall, the Swedish equivalent, is satisfied with slightly lower returns of 8%. I suspect these reflect the status quo in the sector, but do this numbers actually imply? The first figure shows the estimate for how much the production cost of electricity is reduced if instead of discounting with 10% we remove discounting entirely. As you can see, the role of the discount rate is dominant for the low carbon options since they are capital intensive. Expectations for high returns on capital is implicitly a choice to raise the cost of low carbon options relative to fossil fuels. Austerity inspired decision to scrimp capital in particular is not a neutral decision from the perspective of climate policy.

In financial goals the aim is to get sufficiently high ”ROCE” i.e. return on capital employed. If the aim is to maximize ROCE it is done by maximizing the profits and minimizing the capital used. If the business is well established in rather saturated markets, possibilities for increased profits might be limited or predicated on price increases which are harmful to the rest of the economy. If profits stay unchanged, denominator (capital) in the ROCE formula can be reduced by moving to infrastructure with lower capital requirements and by taking more debt which is then invested in the ”next big thing” in the hopes of higher returns.

However, decarbonizing the energy system with current costs implies transition towards a system that requires more capital, not less. In the same time adding more especially wind and solar power into the system will quite rapidly lower the market price producers can expect. This becomes a relevant concern long before the system has been decarbonized. These two things together imply that in the course of the decarbonization returns on the invested capital will move to opposite direction than what, for example, Fortum would desire.

Furthermore, in nearly all climate scenarios many sectors that are currently run by burning fossil fuels, should electrify. Driving such a transition means huge amounts of new low-cost electricity unless the idea is to create one cookie jar for electricity producers guaranteeing 10% returns on capital and then another cookie jar for the sectors to be electrified to guarantee similar returns there. Maybe what this implies is that during the transition returns in the electricity sector should be especially low? Maybe the electricity sector should not be dominated by buzz and brutal capitalism, but be as exciting as watching paint dry?

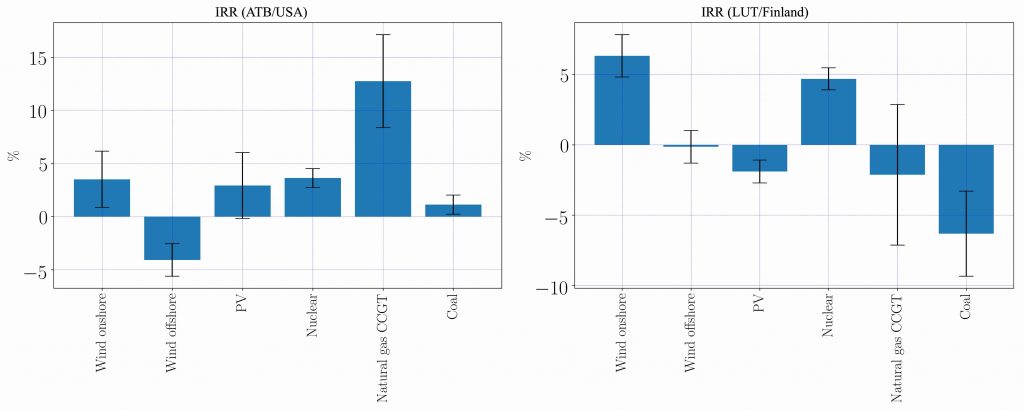

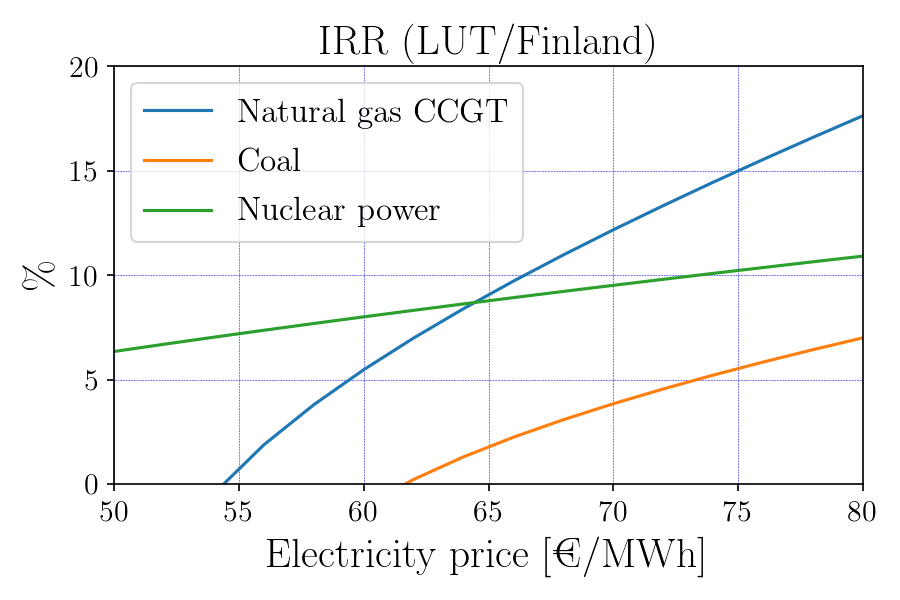

What kind of returns can we expect for different sources of electricity? In the next figure I show quick estimates on the internal rate of return (IRR) for different electricity sources in the USA and in Finland (link to some codes used can be found in the end of the post). IRR is the rate where the net present value of the investment is zero. If you can borrow money at a lower rate, you can make a profit. As can be seen, (in the absence of subsidies) expected 10% returns have been possible mainly from natural gas in the USA. With current electricity prices there are hardly any investments in Finland that would provide expected returns on investments.

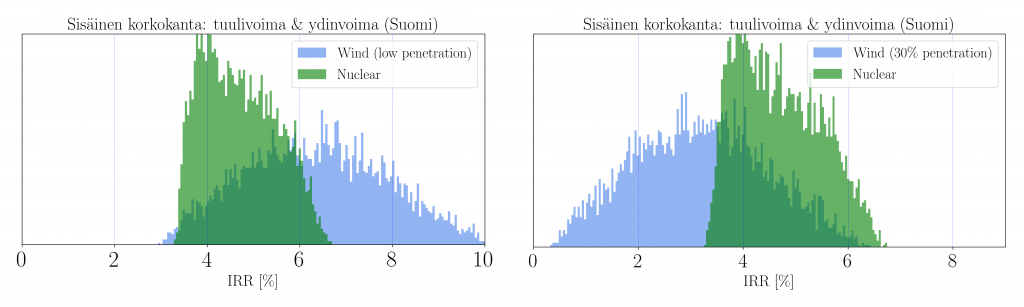

If, in particular, we compare wind power and nuclear power, which might be profitable in Finland we can see the nuclear power is unlikely to ever provide 10% return on investment. If wind power investment is especially successful then fairly high returns are possible, but these drop as the wind power penetration in the system increases. Long before adequate climate action has taken place, returns have become so low that an investor expecting 10% returns will not touch it.

For example, Fortum’s obligations have 2.4% average interest rate. Investments in both wind power and nuclear power could be profitable, but investments in the required scale are not done because they are not profitable enough. Projects are far too cosmetic to make a real difference. Nevertheless, those can be paraded in the PowerPoints and marketing materials to maintain positive vibes among the stakeholders while fast and deep decarbonization of the economy languishes.

Quite often I encounter the narrative of how investors would start building, for example, nuclear power if only politicians would stop obstructing it. For many this narrative is tempting in its harmlessness, but it is likely delusional. Even if the political obstacles would not be there, in the absence of a cookie jar electricity producing nuclear power plants would not be constructed by those looking for 10% returns. Electricity prices would have to roughly double for this to take place. This would obviously have negative consequences for the rest of the economy and would make electrification of the energy system even harder. (An interesting exception here might be a reactor producing only district heating. This would be highly relevant climate action in the Finnish context and could have IRR in excess of 10%. Sources: Värri et al. and Lindroos et al. It could be an interesting project where the desires of those prioritizing climate action might overlap with the desires of the quarterly capitalists.)

In Figure 4 I show how high the expectation for high returns on capital combined with rising electricity prices would likely drive the system towards natural gas since its IRR is very sensitive to market price (as well as gas prices) and rises more steeply that that of capital intensive nuclear power. To stop this would require carbon taxes (or equivalent) that would suppress the improving profitability of natural gas as the electricity prices increase.

Finally we get to the question many have undoubtedly expected — Is this critique of expected returns communism? There are some who essentially claim that anyone questioning the current arrangements or overreactions in any way is a stalinist. If you, for example, suggest market based emissions trading scheme for transport sector, you are still a communist. I find it hard to find ”gulag” in my discussion. There is still a role for investors looking for steady returns over long time periods. For example, I myself would be entirely happy with few percent returns on my savings if they promote serious climate action. No matter what the IRR is, I would not put my money on electricity from natural gas and I hope my pention savings will not be wasted on that either. Those looking for instant gratification should simply move to work elsewhere while more far-sighted grown-ups take the responsibility for the critical task of the decarbonization of the energy sector.

Is this far-sighted actor a state or a private investor happy with lower returns is irrelevant, but the public sector should not (at least without careful justification) create incentives where investors looking for outsized returns can satisfy their sense of entitlement from the public purse with the additional cost of less effective climate policies. Expected returns should adjust to climate policies rather than climate policies adjusting to expected returns. Required incentives should be reserved for those whose time horizon is better suited with the long term climate goals. (In the current system it is also absurd how many market actors are in fact largely state owned. Elsewhere states parade ambitious climate plans while looking from the sidelines as their companies set incentives driving in the opposite direction. It seems that politicians cannot question the structures that were created with political decisions even though that should be their job.)

not compromised.

Greens have a goal to stop climate crises fairly. Part of this overall picture

is the question of how much of our resources are we ready to divert to investors looking for over-sized returns? For example, with current structures market based climate action will only happen with considerable costlier electricity or by investors getting subsidies from the state. In my opinion, this is largely due to exorbitant expected returns. In the following I pose some questions that indicate relevant value decisions rather than

”scientific facts”:

- Why did you choose short time horizon? Who is entitled to the fast bucks it assumes and why?

- Which one do you prioritize, climate goals or existing expected returns? Why?

- If the fast buck is justified, do you want to provide it from the public sector or are other things more important?

- If other things are more important, what does it imply for you? If you have to choose between climate goals and bypassing current marker actors which expect high returns on capital and starting, for example, state-led construction of low carbon infrastructure, which one do you choose? Why?

- Are you ready to use the power of the owner to change the financial goals and incentives of your companies and their leadership so that they are aligned with climate policies? If not, why not?

In this post I think I have quite clearly demonstrated how high expected returns on capital conflict with decarbonization goals as well as with the requirement for a fair transition. This conflict must be resolved before deep decarbonization and the associated electrification of the energy system can seriously start. Maybe Fortum’s financial goals could be rewritten like this?

”Fortum’s financial targets and dividend policy are changed to align with wider decarbonization goals. The long-term over-the-generation financial targets are: Return on capital employed (ROCE) at least 0.1% above the cost of financing. Comparable net debt to EBITDA ratio is whatever is needed to drive fast and deep decarbonization thoughout the economy. If necessary, the state guarantees access to the required capital. Incentive schemes’s for the management are redesigned to reward successful decarbonization.”

Jani-Petri Martikainen

Vice-chairperson for the Green Federation of Science and Technology and lecturer of physics in Aalto University

Sources:

- Some codes and data used to make the figures can be downloaded from the GitHub account for the Green Federation of Science and Technology